In the early 1970s, my parents and I made one of what would be several trips to the former East Germany, also known as the German Democratic Republic, although its name belied its true nature. Our purpose in making this arduous journey was always the same – to give my mother the opportunity to visit two of her dearest friends from her high school days in Kiel, Germany during the late 1920s and early 1930s. One of these dear friends was Hedwig Schmidt, a physician, who happened to be on the eastern side of the wall when it was constructed in 1961.

During that visit in what was likely 1973, we had the pleasure of spending time with not only Hedwig, but her daughter, Jenny, and Jenny’s family. At the time, Jenny and her husband, Peter, had two children, Jan and Lisa. What I remember most about that visit was Jenny and Peter’s strong desire to leave East Germany to pursue the intellectual freedom absent from their lives in East Germany.

Over the years, we have enjoyed several reunions with Jenny and Peter and their children. Lisa Junghanß visited us here in Los Angeles during her studies in the U.S. Today, Lisa Junghanß is a well-known German visual and performance artist with works in exhibitions around the world. She is actively involved in the art scene in Berlin, Germany as a studio manager and, of course, an artist.

Interview by Erika Çilengir, September 2020.

Let’s start by talking about your early childhood growing up in East Germany. Of course, that’s where I first met you as a young child in the 1970s. What was it like growing up in East Germany?

It was definitely very different than growing up now. I was very happy to grow up in a big house in a suburb of Dresden, East Germany. My father is an artist and my mother is a psychiatrist, so it was a somewhat artificial house to grow up in, a little bit hippie style. But if you lived as an artist in the former East Germany, you actually had a bit more control over your world, that is, you were not totally controlled by the government. You had more freedom. You could create an area where you could mostly do what you wanted with a degree of privacy. This was very special for us.

In the part of Dresden where we grew up, there were a lot of very old houses, many in the Tuscan style. Two times a year, my parents held big parties, to which they invited other artists as well as gallery folks and musicians. They kept a very open house. I remember that nearly every day my parents had guests with whom they would discuss politics, do photography, and read poetry, so it was very creative – and I was very influenced by these activities.

That’s fascinating. It interests me, first of all, because you were given a certain amount of freedom to explore and have a place where you could do art, which stands in contrast to such an authoritarian government. It is surprising that the government would embrace this artistic side of people and allow them to do things like that.

In your private space, you could do your own stuff. Rents were very cheap in the former East Germany, so artists didn’t have to earn much money for daily life, which meant it was not as difficult to live as an artist. Yet, you had the feeling of being controlled everywhere you went. We were taught that we should not talk about what my parents did at home or which friends came to visit.

My Dad also organized a political circle, to which people who were against the government came together to discuss their problems or their plans to escape. And because my mother was a psychiatrist, some people would come over in the evenings to talk about friends or family who were in jail for political reasons. These were like secret circles. Growing up in this environment taught me how to express myself in different ways. If you live under a controlled or closed system, you learn to do something against the system, to react to the system.

…if you lived as an artist in the former East Germany, you actually had more control over your world, that is, you were not totally controlled by the government. You could create an area where you could mostly do what you wanted with a degree of privacy. This was very special for us.

What about when you went outside the home and into the community, attending school or visiting friends? Were you basically told that was fine, as long as you didn’t talk about what was happening in the home? It seems like that would be a challenge for a child to understand. So I’m curious as to how that was communicated and whether you found it difficult to abide by those rules, or whether it was just second nature having grown up in that environment.

Yes, that was just how I grew up. I didn’t really think about it. But I did have a best friend with whom I talked about everything. Well, not really everything, not the political stuff, but about other things. But definitely not at school. In fact, twice my parents became very angry when they thought I had shared something from the inner circle because it was dangerous for them. My mother had already been in custody and was later convicted of treason. So that’s why when we left East Germany, we were designated as political refugees with special papers indicating that.

We were also constantly observed by the Stasi (the East German secret police). They monitored our phone calls, so there were only certain rooms in the house where it was safe to speak. So, on the one side, it was kind of a hippie lifestyle in which I grew up with all sorts of very interesting political people. But it was also dangerous because we didn’t know if the government would find out. My parents had friends who went to jail and their children (often friends of mine and my siblings) were then separated from their parents and forced into a Kinderheim (a home for children).

How do you think growing up in East Germany impacted the art you do today?

One of the themes in my art is that of escape, escaping from something. It shows up very often in my little movies. It has to do with the fact that we lived for five years out of our suitcases because we didn’t know when we would be told to move out. Finally, we were given 24 hours to leave the country and we were not allowed to come back, not even to visit. We did that for five years and that does something to your psyche. I had problems being able to focus on one thing at a time. My attention would jump around. Reaching a goal step by step was very difficult.

Was this after your parents had petitioned the government to leave? That is, they had put in a formal request to the government asking to leave.

Yes, I was 12 when my parents submitted the request and I was 17 when we left. It definitely had a significant impact on me growing up under those circumstances. Because of my mother’s treason conviction, it became very dangerous for our whole family. However, the government took its time before allowing us to leave because my mother was a doctor and there was a shortage of doctors in East Germany.

Because of my mother’s treason conviction, it became very dangerous for our whole family. However, the government took its time before allowing us to leave because my mother was a doctor and there was a shortage of doctors in East Germany.

How long after you left East Germany did the wall fall?

Six months later. It was really strange. My family even asked themselves, why did we do everything we did? We lost our home, everything. I also wasn’t allowed to go to high school once my parents asked to leave. That was also true of my elder brother. We lost many years of education. And then it wasn’t easy for me to go back to school once we were in West Germany, because of what I had been through.

Did you try to continue some sort of educational routine at home before you left East Germany?

No. We had to learn a profession, so I studied to be a typist. In East Germany, I had to have a profession to become part of the working class. I did that for about eight months or so before we were told we could leave the country.

Is there anything else you want to mention in terms of how your experiences growing up in East Germany came through in your art?

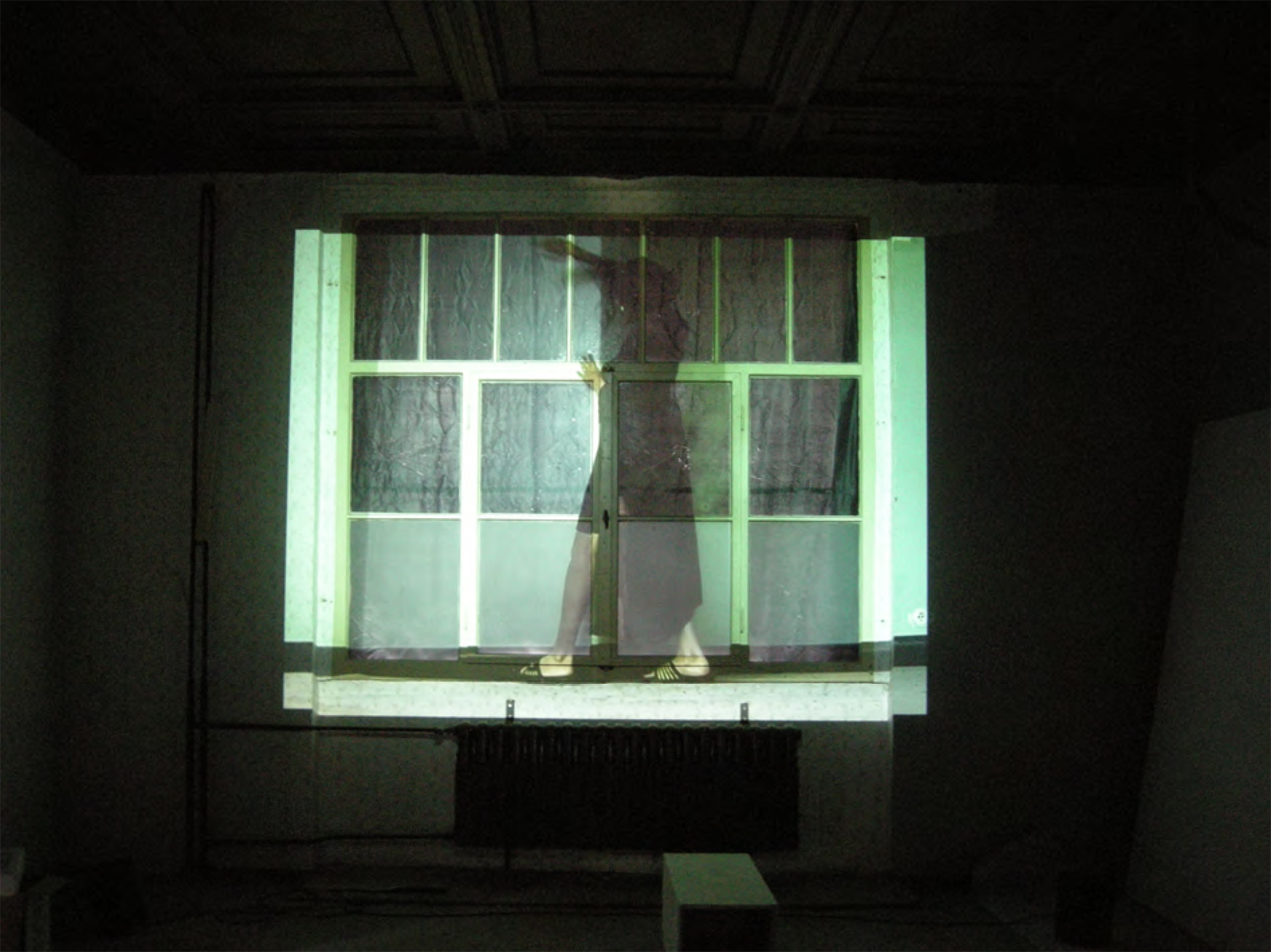

Especially in my movies, you quite often see a person who has been captured or is imprisoned and you do not really know why something has happened to this person. The person unable to get out of the situation. There is a feeling of being unconscious. It is a little bit like the situation we are currently in with the coronavirus. You cannot really do anything to get out of the situation. This theme also came from this time.

Once you came to West Germany, did your family go directly to Augsburg in Bavaria? Was that a place they had already identified as a good place to settle?

Yes, because we had a relative there who offered their house to the six of us. It meant we didn’t have to go to a refugee camp. And then very quickly, my mother found a job at the local hospital because they did not have enough child psychiatrists. My parents had planned to go to Frankfurt am Main, but instead they settled in Augsburg. I would have loved to remain in Augsburg because I love the countryside of southern Bavaria, but when I finished school, as an artist, it made sense to go to Berlin. Now, unfortunately, it has changed, but we will see.

At which point did you realize that art would be your focus? Obviously, you were exposed to art from the time you were very small because of your parents and your father, in particular, and, of course, the many artists who came to your house. But was there a point at which you realized that art would be the focus of your life?

While still in East Germany, I went to a preparatory class at the art academy three times a week beginning when I was 16. So quite early, I was already focused on art. Then I studied communication design for two years. It was at this time that I met artist Martin Eder, who is very successful and well-known internationally. After meeting Martin, I was even more focused on art. We attended art school together after studying communication design (graphic design), which is focused on products, compared with fine art, which is focused on nothing.

What do you do these days? You mentioned that you’re going to a job. Is it related to your art or is it something else entirely?

No, actually, I still work with Martin Eder as a studio manager. I have worked with him for a long time – almost 30 years. We are close friends. For more than five years, we did conceptual art together. We were quite successful with that and were invited to participate in Documenta as well as other large shows. However, because we were a couple at that time, it didn’t work. As I said, though, we are still very good friends and I work for Martin as a studio manager and a private secretary. But, of course, I am also an artist and a mother of two. My various jobs are fun and interesting, including organizing big art shows. My children’s father, Thomas Scheibitz, is also a famous artist, so, all in all, I am quite involved in the art scene here.

I was looking at your CV (resume) and you have clearly had many shows over the years. It is an impressive list.

Yes. However, not a lot of my work is available on the internet because it is really made to be projected in a large space and be part of a staging. It is like a performance that you can step into and become a part of. If you see it on a very small screen, such as a computer screen, you cannot really experience what I intended for you to experience. On the other hand, if nobody sees it, then that is not good either, so I have started to make more of my art accessible via the internet.

Why don’t you talk a little bit about three pivotal points in your life thus far. You’ve talked about what may have been some pivotal periods, such as the period from ages 12 to 17 when you were dealing with so much uncertainty. But what about other points?

Actually, a very important time for me was when I stayed in the United States. After university, I received a stipend to study in New York City for half a year. After that, I attended the Headlands Center for the Arts in Sausalito, California for about four months and stayed with German Artist Thomas Scheibitz. During this time, the September 11 attacks happened, which had a profound impact on my decision as to whether to stay in the United States. I had seriously been thinking about moving to the United States, had a boyfriend in New York, and was very much taken with the country. Every year I came to visit New York, San Francisco, or Los Angeles. But after September 11, I decided this was not the right place to be. I found it very interesting to see how the Americans dealt with the September 11 attacks. I was shocked, actually. It made me wonder what was going on. What did it mean? Why did it happen? Because I grew up in a very political environment, I am very critical of what is happening in the world. I try to get information from many news sources, not just German newspapers, but also the BBC and Al Jazeera – and even the Russians – just to see different perspectives. Even at the Headlands Center, where a lot of intellectual people came together, many could not talk about what was happening. They only discussed what they were working on and their next exhibition. I was disappointed.

I understand because art and politics are very much intertwined. As an artist, it is important to be well-informed and have opinions about things that you express in your art. I don’t know how you can divorce yourself from that.

Yes, that’s my opinion as well. So, finally, I decided to go back to Europe, which was the right thing to do because Berlin was still growing its art scene. Lots of international artists rented studios in Berlin, so it was a very exciting time. I was also a founding member of the producer gallery “record,” a space where 10 artists rented an exhibition space. Everybody paid a certain amount every month. And as an artist group, we hired a gallerist.

Was it like an art collective?

Not really. It’s something special we have here in Germany. When an artist sells a piece of art, the artist gets 50%, the hired gallerist receives 30%, and 20% goes to the gallery owned by the artists.

[After the September 11 attacks,] many could not talk about what was happening. They only discussed what they were working on and their next exhibition. I was disappointed.

Talk a little bit about how your parents influenced your art or the direction that you went in.

Maybe it has to do with the open house they had and the discussions and the interesting people who came, like philosophers, writers, and musicians. I don’t know how they really influenced me. It was more just the way in which we lived, which encouraged me to feel free to express myself as an artist. I started as a painter. I painted for nearly 10 years. That’s why I went to the university in Dresden. The program there was especially good for painting. Most of my friends, even today, are painters. But during my time at the university, I switched to video – moving images rather than static images.

What do you think drew you to moving pictures and away from painting?

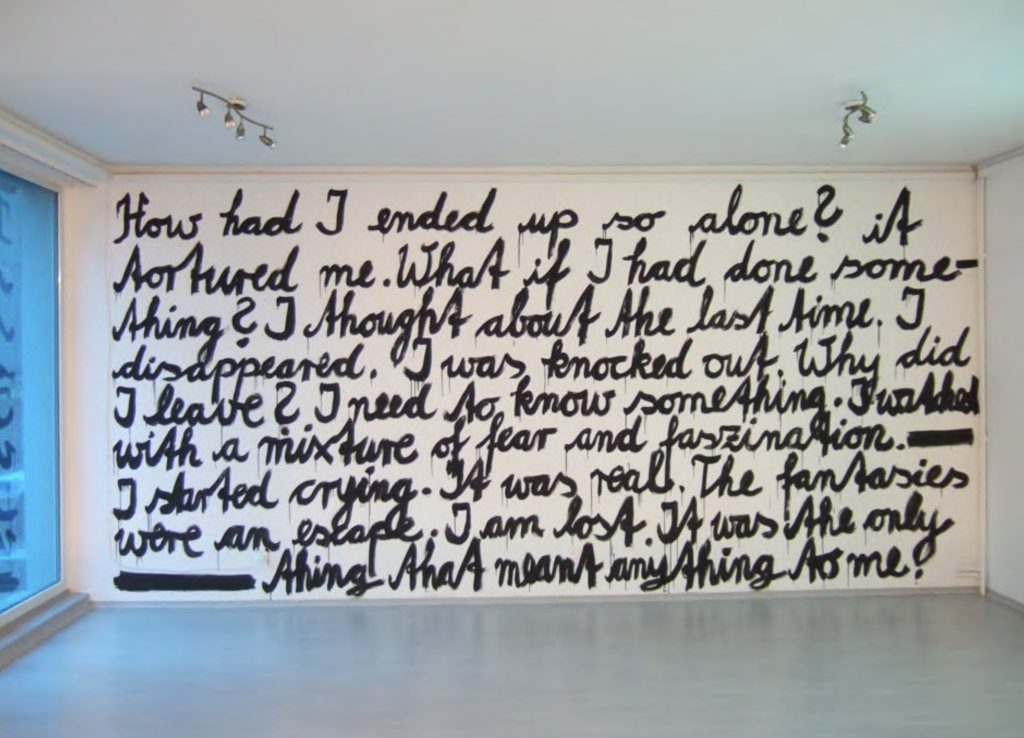

Because I can express myself much better. It has to do with what I want to say. I’m an artist, not a painter. And I’m not just a visual artist. I’m not just a writer. It has to do with the theme or the point I want to express. It depends on how best to express something. It could be as a photograph or it could be as a movie. At the moment, I am doing a lot of writing, but it changes all the time.

What kind of writing are you doing now?

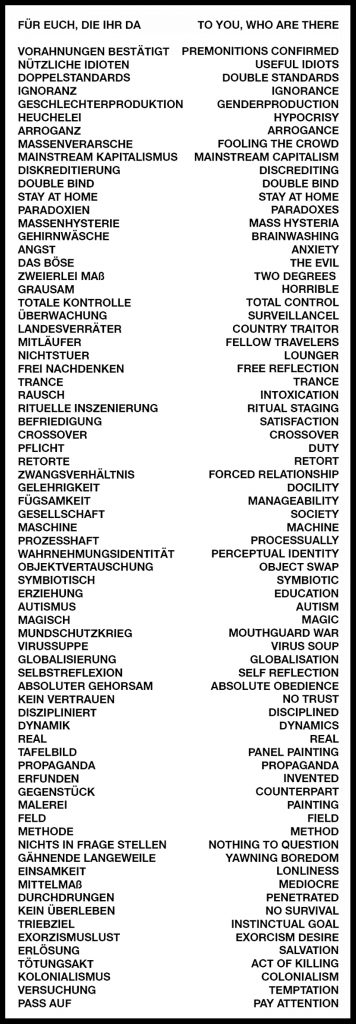

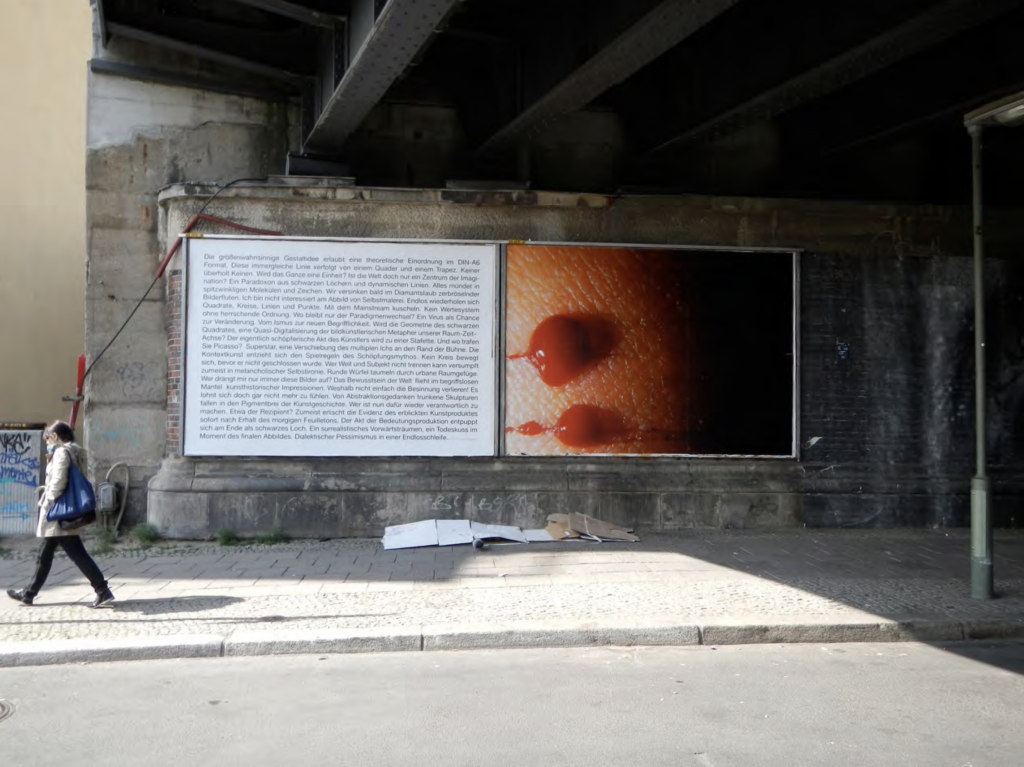

I actually started writing when I was at the university. I wrote little books and short stories and I was quite successful. Then I stopped writing for a while before returning to it about eight years ago. Mostly I do associative texts, which are like philosophical texts. Sometimes I also write about artists, but in a very special way. I also show my texts on billboards in the city and sell them written in my own handwriting. At the moment, writing is more of my medium. I can do it anywhere. I also like my movies, which are quite open. It’s not really a story I am telling. My texts are the same; they don’t really tell a story. They do not have a beginning or an end. And that is the same as with my movies; they are presented in a loop. So it’s a bit more associative and free.

How has your art evolved over the last 20 years? You started out more focused on painting and then you got more into video and other types of media. So talk a little bit more about that.

I decided that showing a picture was more like capturing a snapshot in time. But my aim was to influence the viewer more completely and more physically. That is why I decided to work with video/film, to make it more of a performance. I also do the sound for my films, which I find is necessary to capture my point of view. In my films, I do not work with voice or text. I write text, but it has nothing to do with the movies I create. With film, the idea is to influence people by giving them the opportunity to step into a video installation and become part of the story. You rely on various projections and sounds and that has worked very well. While still in school, I began to find painting boring. It was also a time when everybody thought that painting was on its way out.

Was it also to make it more accessible or to reach a wider audience?

Not really, because I didn’t show my films in cinemas, but rather in galleries or museum spaces. And I didn’t post them on the internet at that time, in part because I started my films in the early 2000s. In the beginning, I came to Dresden to study painting, but after a while it felt very antiquated to me, so I started to do some more conceptual work. Martin Eder and I founded the brand called Novaphorm®, for which we designed a special corporate identity. Under this brand, we created some social sculptures, like a hotel during Documenta X, clubs in museum spaces, and special packaging around a smell to bring certain sensual experiences to people. I spent time thinking about what art was at that moment in the late 1990s. After that, I transitioned to videos/films.

What about during the last couple of years? How has your art changed? Has it been a kind of a continuum or have there been some distinct changes that you’ve made in the media that you use or in the themes you’re addressing?

My primary media are still video and photography as part of some videos, as well as text. For the last five years, I have started to focus on my own history, such as my experiences with the Stasi in the former East Germany. For instance, I created a piece called “Stasi Dialogue” after reading a lot of the records kept by the Stasi on my family and me. In particular, I looked for stereotypes in the texts, from which I constructed special dialogues using a talk show format in which people speak to each other in this particular stereotypical way. Perhaps you know of Victor Klemperer, who wrote “The Language of the Third Reich.” What I did was similar because the Stasi also used a special type of language to talk about people. For example, in their records on my family and me, the Stasi used very funny alias for us, like “cucumber” or “dumpling.” The Stasi also had a huge collection of the smells of people in jars, which they used to search for people with the help of dogs. I also shot some film from the infamous Stasi jail here. So this is the theme I have focused on in the last few years. Perhaps that is because I am now the age my parents were when the wall came down. Interestingly, not many artists from the former East Germany work with this theme.

When you first came to West Germany, did you notice that there were distinct differences between the German that you grew up with versus the German that was spoken in West Germany? Did you notice differences between the two?

Of course. If you read newspapers from the former east and from the west, you can see this. You also see a kind of stereotypical speaking. In fact, our Chancellor Angela Merkel used to use words typical of the German spoken in East Germany, such as durchfuhren, and other bureaucratic language. In East German newspapers, there were also frequent references to Marx and Lenin.

I noticed that earlier this year, you were part of an exhibit called Alptraum that was shown here at the Torrance Art Museum in Los Angeles. Can you tell me a little bit about the exhibition? It appears to have been a traveling exhibition.

Yes, that’s right. It was started by Berlin Artist Markus Sendlinger in 2017. It continues on tour. Artists contribute works around the theme of Alptraum (“nightmare” in English). My contribution was a series I called “Skin Etches,” based on a skin disease I have (another of my themes). I have a library of skin prints, which look very abstract. I often show these as black and white photographs and have exhibited them twice in galleries in London.

My next larger show is in October 2020, a group show, at the Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, which is quite famous. The exhibition is called “In aller Munde” (“in everybody’s mouth” in English). My contribution to that exhibition is text that deals with “oral” things shown as a large poster. In fact, there is a stack of posters, which visitors can take with them. And then in winter, I will have two billboards in Berlin.

So the billboards, how do those work? Is that something that you pay for to have put up?

Yes, I rent them because I like the idea of having a show that is really in the public, for everybody. Not just the artist community.

How long is it up for usually?

Just for one week, usually, because it is expensive.

Do you get feedback? And if you do, how do you get feedback? I’m assuming it’s just an image.

That’s true. Of course, I get the most feedback from people I know. But I do observe people looking at it, although I don’t interview them.

Does it have your name on it?

Yes, it does. Maybe I should put it up on Instagram. It would be interesting.

Is Instagram what you normally use as far as social media to communicate?

Yes, Instagram. But I’m kind of shy, so it is scary for me. I see all the people who post what they are doing and it is rather narcissistic. However, I should definitely do it more.

Could you talk to me more about your formal education and how that influenced your development as an artist?

My study of graphic design influenced me such that when I started to make conceptual art, I used the basics of graphic design I had learned to promote my artwork as a brand. That is, I used what I knew about marketing. When I studied painting in Dresden, we spent the first two years covering the basics, including figure painting every day for two years. We also had to paint still life works, like flowers. I found it very boring, so I started to do different stuff, such as the Novaphorm® pieces, together with Martin Eder. It was very different from what my colleagues were doing and my teachers did not like it at all. In fact, they told me I had to leave school if I insisted on doing it. But by that time we had already been officially invited by Documenta X and it was just my second year at university. Then the university’s art historian said, “No, you cannot throw them out because they are part of the contemporary discourse. Instead, we should ask: What are we studying here in the late 1990s? Perhaps we have to change direction.” However, because I was studying in Dresden, which had been in the former East Germany, many of the instructors were former East Germans and they had no respect for my work. Then they invited younger teachers, artists from West Germany and America, so things improved. I changed classes and had more freedom and could do whatever I want. So it was a funny time and very interesting. At the end, I finished very well and got a stipend to study in New York.

It was very different from what my colleagues were doing and my teachers did not like it at all. In fact, they told me I had to leave school if I insisted on doing it. But by that time we had already been officially invited by Documenta X and it was just my second year at university.

So when you went to New York, how was that experience? What was that like?

It was super because for me, coming from the former East Germany, it was my biggest goal to study in America. I felt a stronger draw to America than to Paris or London or other European countries. I was totally happy. I rented out my apartment and said, OK, goodbye Europe. At the beginning, I expected to stay in the States.

What sort of art did you do when you were in New York?

Videos, very experimental stuff, as well as installations with different objects. New York was really very inspiring for me. To meet all these artists, these international artists, particularly coming from Dresden, and to get a much broader idea of what art could be. In addition, seeing it and living it on my own was a great experience. I also wrote a lot of short stories at that time and did a lot of writing generally. I’m still working on a book that includes short stories, associated texts, and aphorisms. However, it is not easy to lay out because of the different types of writing in the book. During my time in New York, I also started to sell art, including my texts, videos, and photographs. I still sell texts as originals, handwritten.

So are there new artistic paths you are looking at over the next few years? Are there certain themes or media you would like to get into that perhaps you haven’t explored yet?

Yes, at the moment, I am working on a big installation with texts that are projected. Visitors step into a room and are surrounded by sentences from my texts. Text is here, text is there – and they move around; it is more like a show, very associative because it depends where you look from moment to moment. You can also combine the texts as you want. There are colors and sound – electronic sounds. Often I have electronic sounds in my videos or installations, which I compose myself. It’s a bit like stepping into a show with noisy electronic music and these text phrases. Sound is very necessary in my kind of work because sound influences you greatly. If you combine text, colors, and sound, it goes to your brain, so this combination evokes in the viewer a special feeling.

When you’re creating something like what you just described it, do you have a specific goal in mind as far as how you want people to respond to it?

Yes, my goal is to create in someone a special emotion by viewing my art. I really want the viewer to feel insecure, to leave his point of view and get lost in unknown territory. In general, I work with my texts very associatively. In fact, I have a library of texts and videos. It’s more like collage work sometimes. I start with an idea or a scene and then think about how I could best transfer that idea or scene. I then look to my video library and pick some scenes, watch them, and put them together. Mostly I begin by creating the sounds to elicit an emotion because for me sound is the most important thing to create emotions. Then I put the video pieces together and mix them up. It’s also a bit like a big collage.

Currently, I am also working on a very interesting little movie. It is an over-the-shoulder movie that has interested me for a long time because it evokes suspense that something is about to happen. In my movies, you always wonder what’s going on, but nothing really happens. You may feel very uncomfortable, like something is about to happen, but nothing ever does. There’s never a resolution.

What about this period we’re living through right now, this pandemic, in particular? Has that impacted the work that you’re doing in any way?

I’m still in shock, actually, because the whole situation reminds me of the way things were when I was growing up in East Germany. It also reminds me of the September 11 attacks, but this is a virus terrorist attack. I’m also very critical of the way in which the situation is being handled. I don’t totally trust the government’s handling of the pandemic because of my experience growing up in East Germany. It’s really strange. Some of my friends feel the same way, but most of them don’t. We have big discussions on this topic. I feel insecure and unsafe here, and not just because of the virus, but also because of the restrictions and controls imposed to deal with the virus. I am afraid of how governments are reacting and what the impact on democracy will be. In a democracy, it should be possible to think in a critical way about what has happened. You read the newspaper and are told you need a mask, but many don’t think about what’s really going on here and how it affects our children.

Lisa Junghanß’ experiences growing up in East Germany have clearly impacted not only her art, but her worldview. Hers is a particularly important perspective during these times, with the rise of new authoritarian regimes around the world, the strengthening of existing ones, and the erosion of human rights. Those, like Lisa, who have experienced the heavy toll exacted by living under an oppressive government are voices that deserve our attention. It is wise to heed their warnings.